Recently I wrote about David Meltzer's

The Clown and mentioned the connection between Meltzer and the Beat Generation visual artist - collagist, editor, painter, poet, photographer - Wallace Berman.

Earlier I briefly noted poet David Meltzer's 1960 book,

Berman's amazing magazine, Semina, consisted of randomly compiled pages which features the Berman pantheon (Artaud, Cocteau) as well as still-emergent Beat colleagues, Philip Lamantia, Jack Anderson, Patricia Jordan, Kirby Doyle, Bob Kaufman, Aya Tarlow, Ruth Weiss, Michael McClure, John Wieners - as well as already more prominent poets such as Duncan and Ginsberg. To Holland Cotter

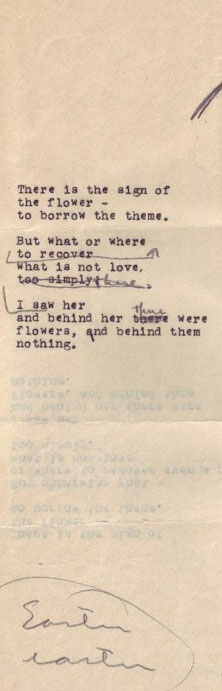

Semina defined "a trippy, sardonic West Coast surrealism." (At left: a detail of a photograph of

Semina #1.)

Cotter was reviewing - very favorably - a January-March 2007 exhibit at the Gray Art Gallery at NYU called "Semina Culture: Wallace Berman & His Circle."

"I would call Wallace a spiritmaker," Michael McClure has said, "a soul-maker, because I don't view

Semina as a poetry magazine. I see

Semina as an assemblage; the visual art in it is as interesting as the poetry. The act of creating it is an act that coincides with the poetry. I tend to look at the production of it. In other words: in the era of the slickest production values, here's probably the least slick magazine or the least slick assemblage that anybody had ever seen" (

Support the Revolution 64).

Berman is shy about his own work but occasionally organized an exhibit to show it. One such show, at Ferus Gallery in LA in 1957, was busted by the cops. Berman himself was arrested "for exhibiting lewd material." (See below.) The piece the policed didn't like was not Berman's but Marjorie Cameron Parsons Kimmel (d. 1995) who went by "Cameron." The offending image had been published in

Semina but copies of the magazine had been scattered on the gallery floor.

It seems that the next Berman show wasn't until 1965.

A 1964 broadside - 5.5" x 8.5" and printed in a small edition - was called

Poetry Is a Muscular Principle. The text of this was written by Michael McClure, with a photo of McClure as a lion made by Wallace Berman, and Berman did the design and the printing.

Semina was eventually nine volumes. It was done in offset printing and also in letterpress printing.

Berman died in Topanga Canyon (north of LA) at the age of 50.

I'm looking at a fabulous exhibit catalogue prepared for

Assemblage in California: Works from the late 50's and early 60's, a show at the U Cal Irvine art gallery in the fall of '68. (Berman was one of six artists featured in the show. Bruce Conner was one of the others.)

Christopher Knight in "Instant Artifacts" writes: "The inventory of pictures [Berman] overlaid over radio speakers is long: an antique bust, a palm-reader's chart, a jazz musician, a thumb, a bird, a one-eyed priest, a snake, a skull, a mandala, a praying cardinal, an engine, a flower, a soldier, a galaxy, a skeleton, a fighter plane, Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, a gun, a dancer, a Hebrew letter, handcuffed wrists, Buck Rogers, a bed, a window, keens, a coat, an ear, a bell tower, an American Indian chief, a Mayan relief, a butterfly with a pocket watch, Mike Jagger, a planet, a copulating couple." This is a Verifax collage.

And a photograph of the Ferus Gallery door after the police raided the Berman exhibit and carried him off to jail:

[]

[] Exhibit catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Art, Amsterdam,

Wallace Berman: Support the Revolution.

[] Exhibit catalogue,

assemblage in california: works for the late 50's and early '60s, Art Gallery, Univ of California at Irvine, 1968.

[] Holland Cotter, "A Return Trip to a Faraway Place Called Underground,"

New York Times, January 26, 2007.

In 1960 Berman started Semina Art Gallery on a houseboat in Larkspur, Marin County. He also that year published the sixth issue of

Semina.

In the rapidly commercializing field of contemporary art, he was a more and more visible presence. He served on exhibition juries, gave interviews, organized and installed the Surrealist group show at D'Arcy Gallery which has already been mentioned here, and accepted invitations to lecture about his work, a feat he discovered he could manage easily. In '60 he was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters (amazing, when you think of how staid that organization was).

In the rapidly commercializing field of contemporary art, he was a more and more visible presence. He served on exhibition juries, gave interviews, organized and installed the Surrealist group show at D'Arcy Gallery which has already been mentioned here, and accepted invitations to lecture about his work, a feat he discovered he could manage easily. In '60 he was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters (amazing, when you think of how staid that organization was).

Is '60 the moment when the end of the end of the Old Left had been reached and the New Left began to emerge? Is it the final ascendancy, in certain scenes at least, of poetic postmodernity? Surely the publication of Donald Allen's The New American Poetry that year suggests this, but then again--once again--we look back on "New" here and see continuity. The rhetoric of the Kennedy-Nixon contest made much less of a dent than everyone (at the time as well as since) claimed, so one wonders why were such great claims made?

Is '60 the moment when the end of the end of the Old Left had been reached and the New Left began to emerge? Is it the final ascendancy, in certain scenes at least, of poetic postmodernity? Surely the publication of Donald Allen's The New American Poetry that year suggests this, but then again--once again--we look back on "New" here and see continuity. The rhetoric of the Kennedy-Nixon contest made much less of a dent than everyone (at the time as well as since) claimed, so one wonders why were such great claims made?  Had we come to expect "1960" to be truly ubiquitously modern in a way that the 1950s really were not--not quite? And what specifically does "modern" mean in the Kennedyesque talk then and now about the torch being passed to a new generation, etc.? The First Lady really meant "modernist" when Camelotians said "modern." What about the others across the new young cultural leadership? I've been surprised by how frequently the

Had we come to expect "1960" to be truly ubiquitously modern in a way that the 1950s really were not--not quite? And what specifically does "modern" mean in the Kennedyesque talk then and now about the torch being passed to a new generation, etc.? The First Lady really meant "modernist" when Camelotians said "modern." What about the others across the new young cultural leadership? I've been surprised by how frequently the  "Beat movement" was covered in 1960 in the mainstream press. I was expecting a fair measure but I've found tonnage. 1960 was the year when the figure of the beat was beginning to find acceptance, although still 80% of these stories are mocking, rebels-without-cause condescension. For anyone whose analysis made an impact nationally, do these antipolitical adolescents count as part of the "new young cultural leadership"? No, but rather than the two being opposites, they fall along a Continuum of the New American. Now that's a change for '60.

"Beat movement" was covered in 1960 in the mainstream press. I was expecting a fair measure but I've found tonnage. 1960 was the year when the figure of the beat was beginning to find acceptance, although still 80% of these stories are mocking, rebels-without-cause condescension. For anyone whose analysis made an impact nationally, do these antipolitical adolescents count as part of the "new young cultural leadership"? No, but rather than the two being opposites, they fall along a Continuum of the New American. Now that's a change for '60.